View Models: POCOs versus DependencyObjects

26 Mar 2009If you’re leveraging the MVVM pattern in your WPF/Silverlight development, you will quickly be faced with a decision regarding the implementation of your view models: should they be DependencyObjects, or POCOs (Plain Old CLR Objects)? I’ve seen and worked with applications that use both of these options.

This post is intended to discuss these two options. It certainly won’t touch on all issues and nuances of either option, but it will cover the main ones I have found to be problematic. I will order them from least significant to most.

Performance

I was hesitant to even mention this one because I haven’t done any measuring and haven’t found it to be a problem at all. There is a theoretical performance benefit to using DependencyObjects for view models for a couple of reasons:

- lower memory usage

- faster binding performance

The former assumes your view models have a lot of properties, and that those properties tend to take on their default values. WPF’s dependency object system is optimised for this case. Your typical WPF control has dozens or even hundreds of properties, most of which are set to their default value. Extra memory is only used by properties if they take on a non-default value. If your view models follow a similar pattern then you might get some memory usage benefits from using DependencyObjects. But I’d also be questioning your view model design if that was the case.

The second point is more relevant, since the primary job of a view model is to provide properties to which the view can bind. WPF’s binding system supposedly performs better when binding to DependencyObjects than to CLR properties. That may well be the case (again, I haven’t measured), but the difference must be negligible because this has not proven to be a problem for me thus far.

Property Change Notification in a Related View Model

Suppose you have two view models that are related. For example, a ParentViewModel and ChildViewModel. Let’s say that the ChildViewModel has a reference to a ParentViewModel. When the Savings property on the ParentViewModel changes, we want to update the Inheritance property on the ChildViewModel. Using DependencyObjects as view models, we can use data binding to achieve this:

//this code is in the ChildViewModel constructor

var binding = new Binding("Savings") { Source = parent};

BindingOperations.SetBinding(this, ChildViewModel.InheritanceProperty, binding);

Using POCOs we need to do a little more work. Typically your POCO view models will implement INotifyPropertyChanged, so the code would look more like this:

//this code is in the ChildViewModel constructor

parent.PropertyChanged += delegate(object sender, PropertyChangedEventArgs e)

{

if (e.PropertyName == "Savings")

{

Inheritance = parent.Savings;

}

};

Neither of these options is particularly appealing to me, but the binding approach with DependencyObjects is more flexible and less typing. Both suffer from magic strings ("Savings", in this case).

Serialization of View Models

Sometimes you will want to serialize your view model. For example, you might want to implement the IEditableObject interface so that changes to your view model can be rolled back. An easy way to do this is to serialize a snapshot of your view model and then roll back if necessary:

[Serializable]

public class MyViewModel : IEditableObject

{

[NonSerialized]

private object[] _copy;

public MyViewModel()

{

Name = string.Empty;

}

public int Age { get; set; }

public string Name { get; set; }

public void BeginEdit()

{

//take a copy of current state

var members = FormatterServices.GetSerializableMembers(GetType());

_copy = FormatterServices.GetObjectData(this, members);

}

public void CancelEdit()

{

//roll back to copy

var members = FormatterServices.GetSerializableMembers(GetType());

FormatterServices.PopulateObjectMembers(this, members, _copy);

}

public void EndEdit()

{

//discard copy

_copy = null;

}

}

This works fine for POCO view models, but not so for DependencyObjects. Recall that for an object to be serializable (and I’m talking strictly about IFormatter-based serialization here), it and all its subclasses must be marked with the Serializable attribute.

DependencyObjects are not marked as serializable.

Incidentally, you might instead follow the pattern where you wrap your data inside a serializable struct and just serialize/restore that struct instead of the view model itself. That works great for POCOs, but – yet again – you will run into headaches if you use DependencyObjects.

And there are other reasons you might want to serialize your view model. Perhaps you want to clone it. Or perhaps you want to save certain view model objects over application restarts. DependencyObject-based view models will cause you grief when this need arises. Basically, your only option is to implement serialization surrogates, or use a non-IFormatter-based serialization mechanism.

Equality and Hashing

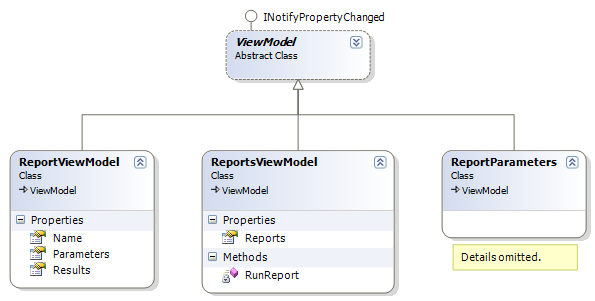

It is often useful to compare view models for equality, or stick them in a dictionary. For example, suppose you have a ReportsViewModel that is responsible for managing and exposing a set of ReportViewModels (note the plural versus singular in those names). Each ReportViewModel contains the name of the report, the parameters to the report, and the results of its execution:

Now suppose you’d like to cache report executions. If the user runs the same report with the same parameters, you’d like to just give them the existing results. To achieve this, you’d naturally attempt to override the Equals() and GetHashCode() methods in the ReportViewModel class (and implement IEquatable<ReportViewModel> if you’re thorough). But if the ReportViewModel class inherits from DependencyObject, you’ll find that you can’t.

The DependencyObject class overrides and seals both the Equals() and GetHashCode() methods.

This inability to redefine equality in your view models is both annoying and limiting in certain scenarios. There may be ways around the problem. For example, you could implement a class that implements IEqualityComparer<ReportViewModel> and use it where appropriate. However, this can quickly lead to a mess and anti-DRY code base.

Of course, if your view model is a POCO, it won’t suffer from this problem. You’d just provide the most appropriate implementation of equality inside your view model class.

Thread Affinity of View Models

One of the responsibilities your view models will typically take on is that of doing heavy work on a background thread. For example, suppose you have a refresh button in your UI that causes a heap of widget data to be loaded from the database and displayed in a list. You’d hardly want the UI to hang while the database access is taking place, so you decide to put the work in a background thread:

public class MyViewModel

{

//this gets called when the user clicks the refresh button - we'll worry about how that happens in a later post

public void LoadWidgets()

{

//do the heavy lifting in a BG thread

ThreadPool.QueueUserWorkItem(delegate

{

var widgets = new List<Widget>();

//pretend I execute a database query here, would you kindly?

var dataReader = command.ExecuteReader();

while (dataReader.Read())

{

widgets.Add(new WidgetViewModel(dataReader["Name"]));

}

//now we have all our widgets read from the DB, so assign to the collection that the UI is bound to

Dispatcher.Invoke(delegate

{

Widgets.Clear();

Widgets.AddRange(widgets);

});

});

}

}

All we’re doing here is doing as much work on a background thread as we can. Only at the last step do we switch to the UI thread to update the collection that the UI thread is bound to (and with the right infrastructure, even that would be optional).

Again, this is great for POCO view models, but falls flat on its face for DependencyObjects.

A DependencyObject has thread affinity - it can only be accessed on the thread on which it was created.

Since we’re creating a bunch of WidgetViewModels on a background thread, those view models will only be accessible on that thread. Therefore, as soon as the UI thread tries to access them (via bindings) an exception will be thrown†.

The only option here is to construct and populate each view model on the UI thread. This is ugly, error-prone, and can negate much of the benefit of doing the work on a background thread in the first place. If we need to create many view models, suddenly the UI thread spends much of its time constructing and initialising those view models.

Code Readability

You’ll notice that all of these problems can be worked around, and I don’t dispute that. However, all those workarounds result in an incomprehensible mess of code. One of the most important qualities of code is its readability. Using DependencyObjects as view models causes an explosion of supporting code and workarounds that obscure the intent of the code. What’s more, all these workarounds gain you . . . nothing.

To me, this is the final nail in the coffin for DependencyObjects as view models. I want my view models to be as readable and maintainable as the XAML I get from using MVVM in the first place. Rather than sweep The Ugly from the view to the view model, I’d much prefer to banish it entirely.

Conclusion

I think the advantages of POCO view models over DependencyObject view models are clear and convincing. Moreover, the disadvantages of using POCOs are practically zero. As such, I always use the POCO option in my projects. That said, all the problems I mentioned can be worked around, and you may have a convincing argument to do so (please let me know in the comments if you do). But, for the here and now, I will be sticking with POCOs for my view models.

In the next two or three posts, I will be sharing some infrastructure I have put together for MVVM applications, starting with a base ViewModel class.

†Note that WPF does do some auto-marshalling for us with simple properties. However, it cannot automatically marshal changes to collections, so you will inevitably end up wanting to create non-trivial DispatcherObjects on the UI thread.